Nova proposta de Gestão de Conteúdo na Web

Este artigo tem por objetivo propor uma nova metodologia de planejamento e gestão de conteúdos na web que sejam otimizados para buscas como alternativa ao modelo focado na intenção de buscas criado pelo Google. Irei criticar o modelo de intenção de buscas, através de uma breve análise histórica da documentação criada pela empresa, tendo como base teórica o paradigma cognitivista das Ciências da Informação.

Irei descrever o processo de busca de informação de Kuhlthau, suas influências e possíveis implicações na criação de conteúdo para a Web, com base no livro Manual de Estudos de Usuário da Informação de Murilo Bastos da Cunha, Sueli Angelica do Amaral e Edmundo Brandão Dantas. E finalmente propor uma metodologia alternativa ao modelo focado em intenção de busca.

Crítica ao modelo por intenção de busca

Atualmente o modelo que procura entender por que as pessoas fazem buscas online, baseado na intenção por trás de cada iniciativa do usuário é um padrão da indústria de criação de conteúdo e do SEO.

Esse modelo, apesar da sua contribuição inequívoca, tem um problema que não foi explorado por profissionais da nossa área: o uso de somente uma dimensão no entendimento do processo de busca de informações (a intenção) não só limita o nosso entendimento como ignora outros aspectos da subjetividade de quem procura por informações, principalmente na web.

Mas antes vamos olhar para o passado e entender como chegamos aqui.

Análise histórica

O Google começou a usar a intenção de busca para tentar prever o que cada busca significava, como podemos analisar na documentação Search Quality Evaluator Guidelines.

Segundo o site Search Engine Journal existe uma ciência por trás do uso da intenção na recuperação da informação na web. O artigo Utilizing Search Intent in Topic Ontology-based User Profile for Web Mining de Xujuan Zhou, Sheng-Tang Wu, Yuefeng Li, Yue Xu, Raymond Y.K. Lau, Peter D. Bruza pesquisa a efetividade nos processos de recuperação da informação. Demonstra que existe um problema no uso de perfis de usuários genéricos nos sistemas de Web Mining, propondo o uso da intenção da busca para enriquecer estes perfis.

A leitura do Abstract da pesquisa nos ajuda a entender melhor:

É de conhecimento geral que levar em consideração os perfis de usuários da Web pode aumentar a eficácia dos sistemas de mineração da Web. No entanto, devido à natureza dinâmica e complexa dos usuários da rede, a aquisição automática de perfis (de usuário) que tragam valor, era muito desafiadora. Os perfis de usuário baseados em ontologia podem fornecer informações sobre os de usuário que são mais precisas. Esta pesquisa enfatiza a aquisição de informações sobre intenções de busca. Este artigo apresenta uma nova abordagem para desenvolver perfis de usuário para pesquisa na Web. O modelo considera as intenções de busca do usuário pelo processo de PTM (Pattern-Taxonomy Model). Experimentos iniciais mostram que o perfil de usuário baseado na intenção de busca é mais valioso do que o perfil de usuário PTM genérico. Desenvolver um perfil de usuário que contenha as intenções de pesquisa do usuário é essencial para uma pesquisa e recuperação eficazes na Web. – Tradução minha.

No documento vimos que pesquisa segmenta a intenção de buscas em dois objetivos, em um nível básico:

- Quando o usuário usa um termo e procura informações específicas sobre esse termo;

- Quando o usuário usa um termo para representar um tópico e, portanto, quer informações mais gerais.

Vamos dar um exemplo simples:

Eu preciso comprar uma nova geladeira para a minha casa. A minha primeira busca pode ser feita usando refrigerador ou geladeiras. Simplesmente porque preciso explorar o assunto.

Depois de procurar em vários lugares, volto na busca e uso um termo mais específico: geladeira 40 litros de inox.

Fica claro que essa pesquisa foi usada como base dos estudos para tentar entender a intenção de buscas dos usuários e qual era o impacto na efetividade da busca.

Quero salientar outro trecho da pesquisa:

Atualmente, a busca na Web não considera a intenção de busca do usuário. A maioria dos mecanismos de busca simplesmente desconsidera o perfil do usuário da Web. Os perfis de usuário são uma importante fonte de metadados para processos de Recuperação de Informações (IR). Para melhorar a precisão e aumentar a eficiência do acesso à informação, o processo de busca na Web precisa evoluir ainda mais com a capacidade de incorporar a intenção de busca do usuário. No entanto, perfis valiosos de usuários da Web são difíceis de adquirir sem intervenção manual.

Quero salientar deste trecho o conceito de precisão na recuperação da informação. Como cita Araújo Júnior em Precisão no processo de busca e recuperação da informação:

A Precisão é um conceito fundamental para a avaliação da qualidade da recuperação da informação, ao mesmo tempo em que representa a medida de interesse (informação útil) do que foi encontrado em um processo de busca e recuperação da informação para o usuário, que qualifica a informação recuperada como útil ou inútil de acordo com as suas necessidades.

No mesmo livro, Araújo Júnior, lembra que Lancaster (1998) define precisão “como a extensão com a qual os itens recuperados em um processo de busca e recuperação da informação em uma base de dados são considerados úteis. A alta precisão é dada quando a maioria ou a totalidade dos itens (…) recuperados for considerada útil. “

O ponto aqui é que devemos ir além do entendimento sobre a página de resultados, se ele retornou os milhões de resultados que deveria retornar e em quantos milissegundos. Precisamos saber se esses resultados foram realmente relevantes para as pessoas que fizeram essas buscas.

Como saber isso? Vamos falar mais sobre isso depois.

Em 2016, Paul Haahr (um dos principais engenheiros de pesquisa do Google e está na empresa há mais de uma década), e Gary Illyes, (Webmaster Trends Analyst), fazem uma apresentação chamada “How Google returns results from a ranking engineer’s perspective” ou “Como o Google retorna resultados da perspectiva de um engenheiro de classificação”, que pode ser vista aqui:

Eu fiz algumas pesquisas e trago um resumo para você:

Na apresentação, Illyes e Haahr fornecem uma visão do ponto de vista dos engenheiros, de como o Google classifica informação, faz mudanças no algoritmo e como esse processo determina a recuperação da informação na SERP, mostrando como é desafiador fornecer os resultados mais relevantes aos usuários.

Nesta apresentação ouvimos falar dos famosos mais de 200 sinais de classificação que determinam a ordem nos resultados de pesquisa e que os algoritmos de pesquisa estão em constante evolução.

Também ouvimos sobre as pequenas alterações nos algoritmos, que são feitas quase diariamente e as atualizações no core, que podem alterar profundamente a SERP.

Apesar da apresentação ser antiga, eu recomendo que a assista, porque ali tem o processo básico de uma ferramenta de recuperação, com os nossos buscadores: rastreio, análise dos documentos rastreados, classificação e recuperação. Isso não muda e não vai mudar.

(Sei que está pensando: e o Google Bard? Bom, ele não é uma ferramenta de recuperação da informação, ele gera informação)

Essa, em resumo, foi a abordagem do estudo que inspirou, podemos dizer assim, o Google a expandir esse modelo e criar as quatro intenções de buscas.

Descrição da documentação do Google

Como é de conhecimento geral, o Google usa revisores humanos para fazer um controle de qualidade nas informações que recupera. E esses avaliadores têm uma documentação extensa que precisam seguir para garantir a qualidade do seu trabalho.

Não tenho a intenção de descrever todos os processos que estão detalhados na documentação (que todo profissional de SEO deve ler). Para o objetivo deste artigo, vamos focar no processo que usa a intenção de busca do usuário.

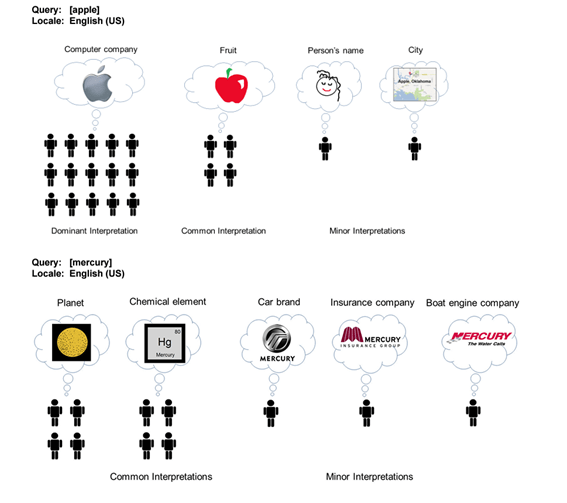

O trecho que quero destacar começa analisando o significado que eles deram ao termo “múltiplos significados de uma busca”, com um exemplo visual, que reproduzo abaixo:

Queries with Multiple Meanings

Many queries have more than one meaning. For example, the query [apple] might refer to the computer brand or the fruit. We will call these possible meanings query interpretations. Dominant Interpretation: The dominant interpretation of a query is what most users mean when they type the query. Not all queries have a dominant interpretation. The dominant interpretation should be clear to you, especially after doing a little web research. Common Interpretation: A common interpretation of a query is what many or some users mean when they type a query. A query can have multiple common interpretations. Minor Interpretations: Sometimes you will find less common interpretations. These are interpretations that few users have in mind. We will call these minor interpretations.

Eles dividem as buscas (consultas) em relação aos significados em quatro segmentos:

- Consultas com vários significados: Muitas consultas têm mais de um significado. Por exemplo, a consulta [maçã] pode se referir à marca do computador ou à fruta. Chamaremos esses possíveis significados de interpretações de consulta.

- Interpretação dominante: A interpretação dominante de uma consulta é o que a maioria dos usuários quer dizer quando digita a consulta. Nem todas as consultas têm uma interpretação dominante. A interpretação dominante deve estar clara para você, especialmente depois de fazer uma pequena pesquisa na web.

- Interpretação comum: Uma interpretação comum de uma consulta é o que muitos ou alguns usuários querem dizer quando digitam uma consulta. Uma consulta pode ter várias interpretações comuns.

- Interpretações menores: Às vezes, você encontrará interpretações menos comuns. São interpretações que poucos usuários têm em mente. Chamaremos essas interpretações menores.

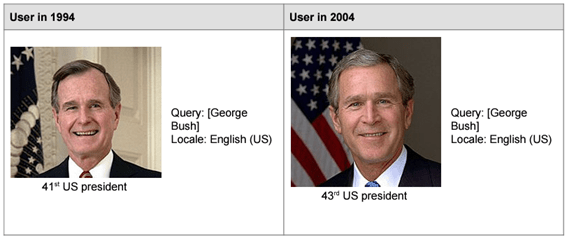

E continuam afirmando que as buscas mudam com o tempo, e nos dão o exemplo do ex-presidente norte americano, o Bush.

Em 1994 a busca por presidente dos Estados Unidos da América retornava informações sobre George Bush. Já em 2004 ela retorna sobre George Bush, mas eles não são as mesmas pessoas. O primeiro era o pai do segundo.

Foi para resolver um problema semântico, para entender qual o significado por trás de cada consulta, é que os engenheiros do Google buscaram uma maneira de entender o que cada busca traz em si, mas que o sistema não conseguia levar em consideração antes.

Procurar entender a intenção por trás de cada busca foi o caminho encontrado. O que naquele momento, com os recursos dos algoritmos, foi a solução adequada.

Na minha visão, levando em consideração os desafios de um buscador, é algo inteligente a ser feito, por ser uma abordagem simples, que reduz a quantidade de variáveis a serem levadas em consideração, é programável e torna o trabalho dos avaliadores mais padronizados.

Como todos sabemos, as intenções usadas pelo Google são:

- Consultas para conhecer algo: algumas das quais são consultas simples das mais conhecidas;

- Consulta para fazer algo: quando o usuário estiver tentando alcançar uma meta ou se envolver em uma atividade;

- Consulta sobre sites: quando o usuário procura um site ou página específica;

- Consultas de visita presencial: algumas das quais procuram uma empresa ou organização específica, outras procuram uma categoria de empresas.

atender todos esses tipos de buscas, procurando entender as intenções das buscas de seus visitantes.

Empresas criaram plataformas que tentam inferir, baseadas nos mais diversos critérios como podem categorizar cada busca dentro dessas quatro intenções, que foram resumidas assim:

- Navegacional;

- Informacional

- Comercial;

- Transacional;

Vejo que a simplicidade desta abordagem é também sua fraqueza. O problema que percebo nesta abordagem é que ela só leva em consideração um aspecto das motivações das pessoas na busca por informação, e a resume sobre o rótulo de intenção, sem nem se dar ao trabalho de definir o que significa intenção para esse modelo.

Este artigo não tem a intenção de debater e nem descobrir o que é intenção para o Google, isso é uma tarefa que seus pesquisadores deveriam ter feito. Ou se fizeram, publicar na documentação. São 371 ocorrências da palavra intent na documentação e nenhuma trata sobre a definição ou o significado do termo.

A ampla divulgação deste modelo do Google gerou no mercado de criação de conteúdo uma corrida cega, uma busca desenfreada por entender a intenção do usuário, sem se dar o trabalho de refletir sobre o que realmente significa isso.

Crítica ao modelo

Como já tratei brevemente anteriormente neste texto, entendo que o modelo de intenção de buscas foi importante por seu pioneirismo, mas que tem pontos fracos que podem ser resolvidos com o uso de modelos mais robustos.

Preciso levantar um ponto que para mim nos auxilia muito no entendimento sobre o processo de busca por informação.

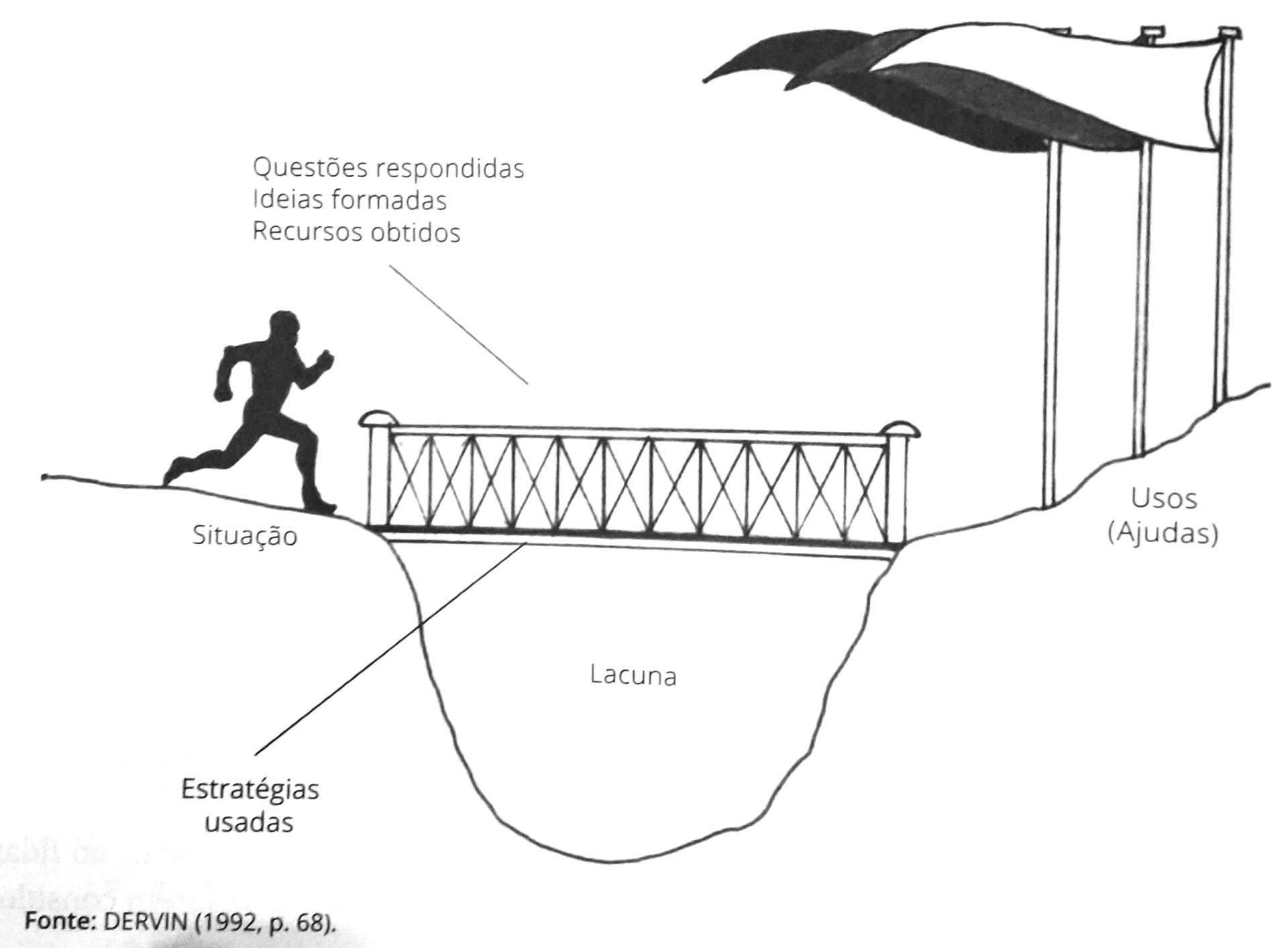

O início deste processo é disparado pelo que Brenda Dervin chamou, em 1983, de vazio cognitivo, que acontece quando estamos numa situação em que as respostas que temos para as nossas questões já não são suficientes para preencher essa lacuna entre o que sabemos e o que precisamos saber.

Extraído do livro Manual de Estudos de Usuário da Informação

Esse sentimento de incerteza, nos levando a vagar na busca por informações que já existem, mas não estão no nosso conjunto de informações conhecidas.

O entendimento sobre as intenções de buscas não leva em consideração esse vazio e nem os sentimentos que são disparados por ele.

Portanto, este artigo propõe uma alternativa a esse modelo, baseando-se no trabalho de uma pesquisadora e educadora americana, Carol Kuhlthau por entender a importância da identificação das necessidades de informação dos diversos segmentos de usuários.

A identificação das necessidades de informação do usuário é o ponto vital da minha proposta e concordamos com Cunha (2015) quando ele afirma que esse é um passo vital para o entendimento dos objetivos estratégicos e preponderantes na delimitação da política de desenvolvimento de acervo e para saber se as demandas são atendidas (grifos meus).

Em nosso ambiente de trabalho precisamos entender que o acervo são todos os tipos de conteúdo criados e postos à disposição para os usuários (atuais, potenciais e não usuários) acessarem.

Portanto, novamente trazendo estudos das Ciências da Informação para o nosso mercado de trabalho: precisamos entender as necessidades de informação de quem está buscando por aquilo que estamos ofertando na web, já que os conteúdos que publicamos nesta rede são o nosso acervo, que precisam de políticas mais adequadas para o seu desenvolvimento.

Este artigo não trata deste amplo assunto, mas faz uso do modelo criado por Kuhlthau para iniciar esse processo.

Quem é Carol Kuhlthau?

Carol Collier Kuhlthau (nascida em 2 de dezembro de 1937) é uma educadora americana aposentada, pesquisadora e palestrante internacional sobre aprendizado em bibliotecas escolares, alfabetização informacional e comportamento de busca de informações.

Biografia

Kuhlthau nasceu em New Brunswick, New Jersey, EUA. Kuhlthau formou-se na Kean University em 1959. Ela completou um mestrado em Biblioteconomia na Rutgers University em 1974 e um doutorado em Educação em 1983. Ela estava no Departamento de Biblioteca e Informação da Rutgers University Professor de ciências por mais de 20 anos e é professor emérito desde 2006.

Carol Kuhlthau fundou o Center for International Scholarship in School Libraries.

Processo de busca da informação de Kuhlthau

Em termos teóricos esse artigo, e as propostas que fazemos nele, estão ligadas ao paradigma cognitivista, no qual Ellis, Dervin, Kuhlthau e Wilson são os pesquisadores escolhidos como base.

Alertamos que é preciso tomar o cuidado de não inovar na teoria e repetir os modelos anteriores na aplicação, como alerta Carlos Alberto Ávila Araújo em seu texto Estudos de usuários: pluralidade teórica, diversidade de objetos na página 8:

O modelo cognitivo destes estudos, ao privilegiar o entendimento da necessidade de informação a partir de uma lacuna, de uma ausência de determinado conhecimento para executar determinada atividade, acaba por engessar uma forma de compreensão dos usuários como seres dotados de uma necessidade específica que seria satisfeita por uma fonte de informação específica.

Por isso esse artigo, além de contrapor o modelo de criação de conteúdo para a web com base na intenção de busca a nossa proposta, propõe um novo modelo de criação de conteúdo, que precisa ser testado e validado na prática.

Influência de Jean Piaget e Brenda Dervin em Kuhlthau

Em 1991, o modelo de Kuhlthau foi introduzido com o nome de Processo de Busca de Informação (ISP). Ele descreve como sentimentos, pensamentos e ações estão presentes em seis estágios de busca de informação.

O modelo ISP é baseado no trabalho de Jean Piaget, ou seja, nos quatro estágios de desenvolvimento cognitivo em crianças, a saber: sensório-motor, pré-operatório, operatório concreto e operatório formal.

Kuhlthau introduziu a experiência holística de busca de informações através da perspectiva do indivíduo, enfatizando o papel vital do afeto na busca de informações e propôs o princípio de incerteza como uma estrutura conceitual para bibliotecas e serviços de informação.

Eu entendo que um buscador se enquadra na categoria de serviços de informação.

O trabalho de Kuhlthau está entre os mais citados pelos professores de biblioteconomia e ciência da informação e é uma das conceituações mais usadas pelos pesquisadores da área.

O modelo ISP representa um divisor de águas no desenvolvimento de novas estratégias para o entendimento de como as pessoas buscam por informação.

Processo de Busca de Informação (ISP)

Também no âmbito da abordagem alternativa, Carol Kuhlthau (1991) defendeu o processo construtivista (Constructive Process Approach) para realizar estudos de usuários e desenvolveu o modelo do processo de busca da informação (Information Search Process – ISP), representado na Figura abaixo, extraída do livro Manual de Estudos de Usuário da Informação.

Figura 5.8 – Processo de busca de informação

| Estágios no ISP | Sentimentos a cada estágio | Pensamentos a cada estágio | Ações a cada estágio | Tarefas apropriadas |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Iniciaçãoe-column-delimiter/>Incerteza | Geral/Vago | Busca de informações preexistentes | Reconhecimento | |

| 2. Seleção | Otimismo | Identificação | ||

| 3. Exploração | Confusão/frustração/Dúvida | Busca de informação relevante | Investigação | |

| 4. Formulação | Clareza | Direcionado/Claro | Formulação | |

| 5. Coleta | Senso de direção/Confiança | Aumento de interesse | Busca de informação focada ou relevante | Conexão |

| 6. Apresentação | Alívio/Satisfação ou Desapontamento | Claro ou focado | Complementação |

Para as autoras, durante o processo de busca da informação (princípio de incerteza), Kuhlthau considera que o nível de incerteza é flutuante e pode ser observado em seis estágios, divididos em três campos de experiência: emocional, cognitivo e físico:

- O estágio de iniciação, quando há o reconhecimento da necessidade de informação;

- O estágio de seleção inicia o trabalho de delimitar o campo ou tema de investigação;

- O estágio de exploração dos documentos acerca do tema, levando a uma expansão do tema geral (por exemplo, a leitura das fontes secundárias);

- O estágio de formulação, no qual ocorre o estabelecimento de foco ou perspectiva do problema;

- O estágio de coleta por meio da interação com sistemas e serviços de informação para a reunião de informações;

- E o estágio de apresentação, o “fim” da busca e “solução” do problema.

Segundo González-Teruel (2005, p. 72), o modelo do processo de busca de informação de Kuhlthau identifica a necessidade de informação com o estado de incerteza que comumente causa ansiedade e falta de confiança. Para a pesquisadora, a incerteza é um estado natural, principalmente nas primeiras etapas do processo de busca de informação.

Rolim e Cendón (2013) defendem que as etapas podem ser visualizadas a partir do caráter dinâmico do processo de busca da informação, pois neste processo há construção de conhecimento e significado. A formulação de um foco de interesse afeta o processo de busca, pois para se estabelecer o foco é preciso interpretar as informações existentes. A natureza da informação encontrada altera a posição do usuário, pois se a informação é redundante pode gerar aborrecimento, mas uma nova informação pode exigir uma reconfiguração de conhecimentos não disponíveis, causando ansiedade. A atitude do usuário influencia o resultado da busca, pois sua busca implica em escolhas pessoais e o interesse aumenta à medida que o foco é definido e a pesquisa avança.

É interessante perceber nesse trecho a reciprocidade entre nossas necessidades e o que conseguimos encontrar quando efetivamos uma busca por alguma informação para suprir essas necessidades. Sentimentos como ansiedade, frustração, aborrecimento, entusiasmo, euforia e alegria não são normalmente levados em consideração quando estudamos as buscas dos nossos visitantes, mas elas fazem parte de cada indivíduo que procura.

Proposta de uma nova metodologia de planejamento de conteúdos otimizados para buscas

Baseado nessa abordagem é que descrevemos e propomos um novo modelo de criação de conteúdo baseado na pesquisa de Kuhlthau (1991), que descrevo melhor abaixo. Antes quero fazer detalhamento para explicitar alguns pontos importantes, principalmente porque o modelo que eu descrevo é uma adaptação do trabalho de Kuhlthau.

Adaptação do processo de busca de informação

Na tabela abaixo, em verde, estão as etapas selecionadas por mim para a adaptação do ISP para criação de conteúdos otimizados para buscas.

| Estágios no ISP | Sentimentos a cada estágio | Pensamentos a cada estágio | Ações a cada estágio | Tarefas apropriadas |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iniciação | Incerteza | Geral/Vago | Busca de informações preexistentes | Reconhecimento |

| Seleção | Otimismo | Identificação | ||

| Exploração | Confusão/frustração/Dúvida | Busca de informação relevante | Investigação | |

| Formulação | Clareza | Direcionado/Claro | Formulação | |

| Coleta | Senso de direção/Confiança | Aumento de interesse | Busca de informação focada ou relevante | Conexão |

| Apresentação | Alívio/Satisfação ou Desapontamento | Claro ou focado | Complementação |

A intenção é propor uma nova forma de planejar a criação de conteúdo baseado em três estágios do processo da tabela “Processo de busca de informação” proposto por Kuhlthau:

- Iniciação;

- Exploração;

- Coleta.

Todas as seis fases estão presentes em qualquer processo de busca de informação, mas a meu ver as fases que selecionei estão perfeitamente alinhadas com a gestão de conteúdo na web.

Entendo que esse modelo permite a criação de uma estrutura que alinha a criação com as necessidades dos nossos usuários, alinhando-as a um processo de gestão e criação que ajuda a satisfazer essas necessidades informacionais, em cada etapa da busca.

A nossa proposta visa considerar a importância das necessidades, desejos, demandas, expectativas, atitudes, comportamentos e demais práticas no uso da informação pelos usuários que buscam por informações as quais os criadores podem fornecer em seus conteúdos.

Mas em contraponto, citamos Hewins (1990) apud Cunha (2015) para salientar que

existem características únicas para cada usuário e outras que são comuns a vários, por isso, será preciso que os sistemas sejam desenvolvidos considerando a flexibilidade necessário para que sejam adaptáveis a todos os usuários.

É claro que Hewins tratava dos sistemas de recuperação de informação, mas podemos ampliar esse sentido e dizer que para que a nossa proposta seja minimamente eficaz precisamos desenvolver um modelo que possa ser adaptado aos dois casos: públicos específicos e uma audiência geral.

Taylor em 1968, falando sobre as questões que os usuários de bibliotecas faziam estabeleceu uma relação interessante entre as perguntas feitas e as reais necessidades dos usuários.

Esse trabalho gerou uma classificação das necessidades de informação que é interessante para o nosso trabalho:

- visceral,

- consciente,

- formalizada,

- comprometida.

Necessidade visceral

Pode estar relacionada com uma vaga insatisfação, mas esse sentimento não é forte o suficiente para gerar uma pergunta. Mas esse estado pode mudar se a pessoa tiver acesso a alguma informação que mude esse sentimento e a incentive a fazer o questionamento.

Necessidade Consciente

Existe uma confusão em nível mental que de certo modo influencia na formulação da pergunta.

Necessidade Formalizada

Quando o indivíduo consegue resolver em certo grau essa confusão, formula o questionamento que dispara o processo de busca por informação.

Necessidade Comprometida

É o questionamento que foi modificado ou reelaborado para que possa ser compreendido por um sistema de informação que não consegue lidar, por exemplo, com busca em linguagem natural. Aqui o usuário precisa se adaptar ao sistema e não o contrário.

Quando Kotler (2000, p. 43) trata do assunto do ponto de vista do marketing alerta que existem esses cinco tipos de necessidades:

- necessidades declaradas (o cliente quer uma TV barata);

- necessidades reais (o cliente quer uma TV que dure muito tempo, mas não se importa com o preço);

- necessidades não declaradas (o cliente espera um bom atendimento por parte do vendedor);

- necessidades de “algo mais” (o cliente gostaria que o vendedor incluísse um som como brinde);

- necessidades secretas (o cliente quer ser visto pelos amigos como um consumidor inteligente).

Com isso em vista, criamos o modelo abaixo que tem por objetivo ser uma base para gerar modelos para gestão e criação de conteúdo que levem em consideração as fases já descritas por nós: a iniciação, exploração e coleta da informação.

Gostaria de lembrar que o mais importante não é o modelo, que pode e deve ser adaptado, atualizado e melhorado constantemente, mas sim um novo pensamento sobre como criamos conteúdo na web.

Um novo tipo de paradigma que seja motivado pelas necessidades das pessoas que precisam dos serviços e produtos que sua empresa quer entregar a elas.

Quero relembrar a nossa base teórica para a criação do modelo abaixo, com essa tabela:

| Estágios no ISP | Sentimentos a cada estágio | Pensamentos a cada estágio | Ações a cada estágio | Tarefas apropriadas |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iniciação | Incerteza | Geral/Vago | Busca de informações preexistentes | Reconhecimento |

| Exploração | Confusão/frustração/Dúvida | Busca de informação relevante | Investigação | |

| Coleta | Senso de direção/Confiança | Aumento de interesse | Busca de informação focada ou relevante | Conexão |

Modelo de criação de briefings

Criar conteúdo {RESOLUÇÃO DO SENTIMENTO} que geram {TAREFAS APROPRIADAS} sobre {AÇÕES} visando diminuir {SENTIMENTOS} que os visitantes que estão no estágio de {ESTÁGIO} sentem.

Exemplo:

Criar conteúdo, específicos e pontuais, que gerem reconhecimento sobre informações preexistentes visando diminuir a incerteza que os visitantes que estão no estágio de iniciação sentem.

O modelo abaixo deve ser usado na geração de briefings de conteúdo com o objetivo de criação alinhada com os sentimentos dos usuários, o estágio que se encontram e como seu conteúdo deve ser gerado para suprir essas necessidades.

Concluindo. Por enquanto.

Para concluir essa primeira versão da minha proposta que conecta o SEO, Gestão de Conteúdos e o Modelo ISP, quero dizer que nós que trabalhamos com e na Web temos muito a aprender com a Biblioteconomia e as Ciências da Informação.

Existe um enorme arcabouço de conhecimentos gerados em séculos de estudos nesta área que são intimamente ligados ao nosso fazer. Entender essa conexão é que me levou, com quase 50 anos a entrar novamente na universidade e fazer um outro curso.

Essa é a minha missão desde o dia que fiz a minha primeira aula: conectar esses dois mundos.